Nigeria's informal sector is the nation's economic powerhouse, providing livelihoods for most of its population and contributing significantly to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Far from being a "shadow economy," it is a dynamic system, with its informal logistics networks acting as crucial arteries for economic activity.

The Informal

Economy: A Core Economic Driver

The informal economy is a dominant force in Nigeria, contributing over 50% to the nation's GDP and employing over 90% of its workforce. This sector encompasses diverse activities, from market traders and street vendors to small-scale manufacturers. The National Bureau of Statistics reported that informal workers constituted 92.7% of the workforce in Q1 2024. This vast ecosystem serves as a vital buffer against unemployment, offering a critical safety net where formal systems are lacking. Policy approaches that dismiss this sector as a "problem" overlook its fundamental role in Nigeria's economic reality and often lead to ineffective top-down initiatives.

Genesis of Informal Logistics: A Necessary

Response

The widespread presence of informal logistics networks in Nigeria is a

direct consequence of long-standing inadequacies in formal state

infrastructure. Decades of insufficient public transportation and logistics

provisions have created a significant gap in mobility, particularly for a

rapidly urbanizing population. This void has been filled by a multitude of

private entrepreneurs who have developed a self-organizing system that now

handles an estimated 70% to 80% of all motorized urban trips in major centers.

The informal system's competitive advantages lie in its flexibility,

responsiveness to demand, and ability to access areas inaccessible to larger,

formal vehicles.

Key

Characteristics of the Network

Nigeria's informal logistics networks operate with distinct

characteristics adapted to their environment:

Cash

Transactions: Cash remains the preferred method of exchange due to

unreliable digital infrastructure and low trust in formal financial systems.

While facilitating quick transactions, this reliance poses challenges for

record-keeping and formal financial integration.

Limited

Formal Record-Keeping: Most informal businesses maintain minimal

comprehensive accounting records, hindering formal performance assessment and

access to traditional credit.

High

Adaptability: These businesses, including logistics operators,

demonstrate remarkable agility in adjusting services, pricing, and operations

in response to market changes, customer needs, or regulatory pressures, crucial

for navigating Nigeria's volatile economic climate.

Reliance on

Social Networks and Trust: Strong social networks and trust-based

relationships form the bedrock of the informal economy, acting as a crucial

substitute for formal legal and contractual enforcement. Local trade

associations and unions play a pivotal role in information sharing, dispute

resolution, and self-regulation.

Urban

Arteries: Mobility and Micro-Logistics

Nigeria's cities, especially Lagos, are characterized by the constant

movement driven by informal transport networks. These urban arteries comprise

various modes, a unique economic model, and a hierarchical human ecosystem.

Modes of

Operation: Danfo, Okada, and Keke

Three iconic informal vehicles dominate the urban transport landscape,

collectively responsible for an estimated 70-80% of all motorized passenger

trips in major cities:

Danfo (Minibuses): These yellow minibuses form the backbone of

high-capacity transit on main urban corridors in Lagos, filling the gap left by

insufficient formal public transport.

Okada (Motorcycle Taxis): Valued for their speed and agility, Okadas

navigate traffic and unpaved roads, providing critical point-to-point and

last-mile connectivity.

Keke (Tricycles): Also known as Keke Marwa, these three-wheeled vehicles offer a balance of safety and capacity, maneuvering through congested streets and accessing areas not served by buses.

The

"Target System": Precarious Efficiency

Many urban informal transport operators adhere to a "target system." Drivers lease vehicles daily from owners, obligated to remit a fixed "target" sum regardless of total earnings. Their income is what remains after paying the target and covering operational costs like fuel, conductor wages, and union levies. This intense daily financial pressure incentivizes behaviors like aggressive driving, vehicle overloading, and abrupt stops to maximize passenger volume, leading to visible inefficiencies and safety concerns. This system's issues are thus predictable outcomes of its core economic model.

The Human

Ecosystem: Control and Extraction

The informal transport sector is supported by a complex human hierarchy

that facilitates operations but also institutionalizes value extraction. The

National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), formed in 1978, acts as a

powerful, quasi-state institution, de facto controlling most motor parks and

routes. While providing some order and protecting members, it is associated

with corruption and often uses informal agents ("agbero") to enforce

revenue collection. This dual role makes the NURTW essential to the system's

stability yet an obstacle to formal reform.

Case Study:

The Lagos Market Supply Chain

Lagos market women exemplify the challenges within this informal

logistics network. They rely entirely on informal transport to move goods from

regional markets to their stalls. Key challenges include:

High

Transport Costs: These costs disproportionately consume profits,

often exceeding 15% of monthly income, inflated by premium charges for goods

and traffic congestion.

Lack of

Suitable Public Transport: Formal buses often prohibit freight, forcing

reliance on informal vehicles at inconvenient hours (e.g., 4 am to 6 am).

Security

Risks: Early morning journeys expose them to significant risks, including

robbery. These hurdles impact business viability and consumer food prices.

Rural-Urban

Lifeline: Agricultural Supply Chains

Nigeria's informal logistics networks are vital for connecting agricultural heartlands with urban consumption centers, moving vast quantities of food across the country. This rural-urban supply chain heavily depends on informal operators.

Mapping the

Flow: North to South

Most staple crops and fresh produce in Nigeria, such as tomatoes,

peppers, onions, yams, grains, and cattle, are cultivated in the northern

states but consumed in the densely populated southern cities like Lagos,

Ibadan, and Port Harcourt. For instance, a major flow of tomatoes travels from

Kaduna State to southwestern states. This north-south road transport axis is

critical due to the near absence of a functional freight rail network. This

heavy reliance on road transport creates systemic vulnerability; disruptions

from poor infrastructure or security incidents immediately affect food

availability and prices in urban centers. This vulnerability was highlighted in

February 2021 when the Amalgamated Union of Foodstuff and Cattle Dealers of

Nigeria organized a blockade, stopping food movement from north to south.

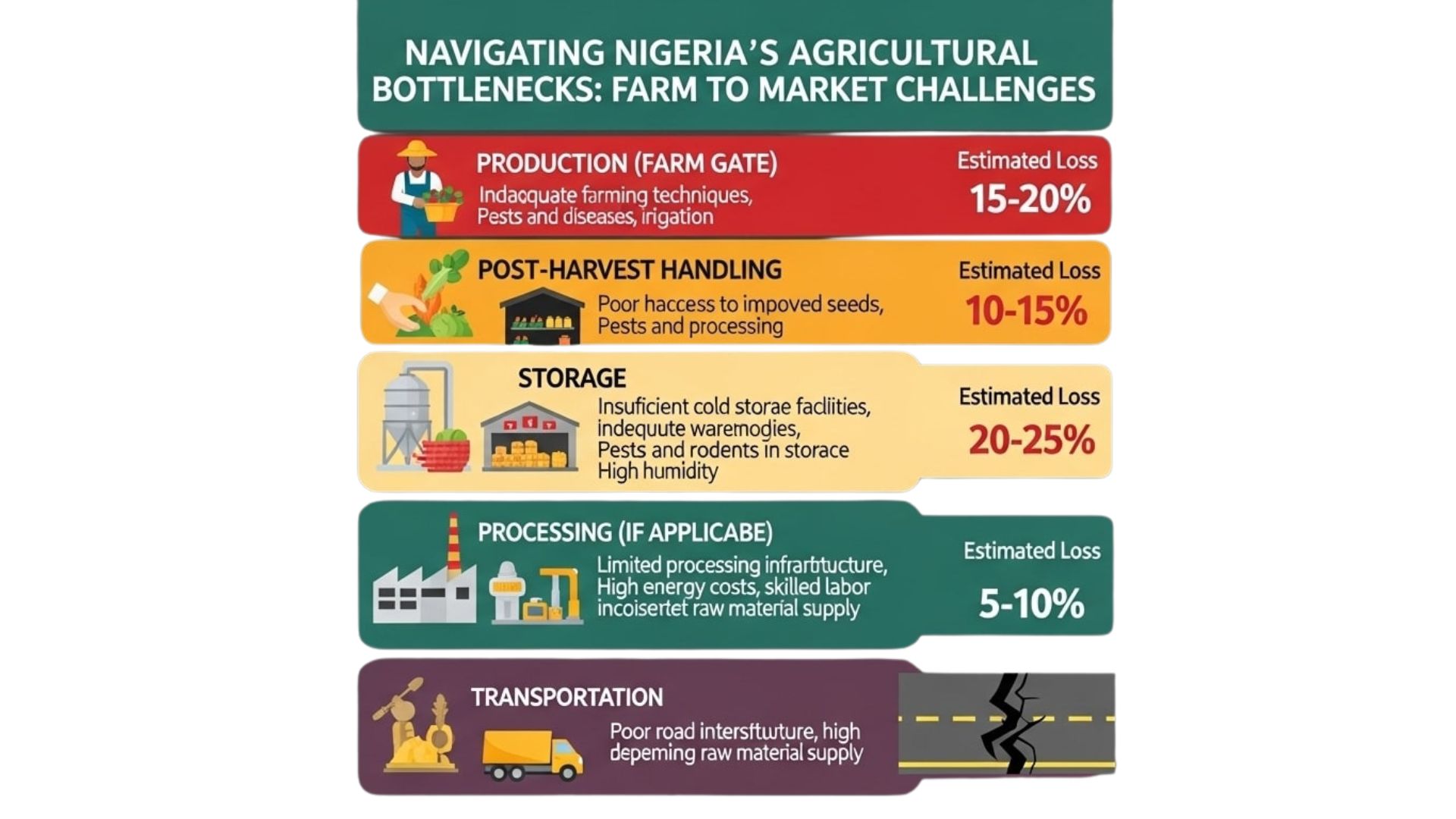

Bottleneck Analysis: A Chain of Inefficiency

The agricultural supply chain is plagued by interconnected bottlenecks

that raise costs and degrade product quality. Post-harvest losses for

perishable goods like fruits and vegetables are staggering, ranging from 30-50%

and even up to 40-70% for some items.

Key

inefficiencies include:

Farm Gate: Lack of on-farm storage and poor access roads lead to low

farm-gate prices and immediate quality degradation.

Rural

Aggregation: Inadequate local storage and poor handling practices

result in value capture by middlemen and mechanical damage.

Inter-Regional

Transit: Deplorable road conditions, numerous official and unofficial

checkpoints leading to extortion, and a severe lack of cold chain

infrastructure significantly increase transit times (a 12-hour journey can take

2-3 days) and costs. Less than 10% of fresh produce in Nigeria moves through a

cold chain. Security risks like theft and harassment further compound issues.

Urban

Wholesale/Deconsolidation: Congestion and inefficient unloading at urban

markets cause further delays and spoilage.

Last-Mile

Distribution: High intra-city transport costs, reliance on

inefficient informal vehicles, and traffic congestion add a final layer of cost

and quality degradation.

Key Actors:

"Charter-men" and Middlemen

Two main informal actor groups manage this supply chain:

"Charter-men": These

owner-operators of trucks and lorries form the backbone of commodity transport,

navigating difficult roads and security risks. They are often regulated by

informal guilds.

Middlemen: Essential

intermediaries who aggregate produce, provide cash to farmers, and manage

logistics. Their market power often allows them to buy produce at low farm-gate

prices, capturing significant profit and contributing to farmer impoverishment.

Last-Mile Delivery (LMD) in the Digital Age

Nigeria's booming e-commerce sector, with projected revenues reaching

approximately $10.00 billion by 2029, has created intense demand for last-mile

delivery. LMD is crucial for customer satisfaction; as high as 85% of online

shoppers would not make a repeat purchase after a poor delivery experience.

Navigating the Urban Maze: LMD Challenges

Informal operators, primarily Okada and Keke riders, form the de facto

LMD workforce in Nigeria's dense urban environments, valued for their ability

to navigate traffic. However, structural deficiencies hinder efficiency:

Inaccurate

Addressing Systems: The lack of standardized addressing means deliveries

rely on landmarks and multiple phone calls, proving inefficient and

time-consuming.

Traffic

Congestion: Severe traffic in megacities like Lagos leads to unpredictable

delivery times and increased operational costs.

Payment and Trust Issues: The prevalence of Cash-on-Delivery (COD) increases failed delivery rates and security risks for riders carrying cash.

This collision of digital economy precision and physical world

informality creates immense friction, driving high costs and delays.

Technology, such as GPS pins for digital addresses, is increasingly being

deployed to bridge this gap.

The Rural Divide: Amplified LMD Challenges

LMD is significantly more challenging in rural areas, where

infrastructure and technology deficits are magnified. Undeveloped and poorly

maintained rural road networks make physical access difficult and expensive,

creating a prohibitive barrier for many e-commerce and logistics companies,

thus deepening the urban-rural economic and digital divide.

The emergence of digital logistics platforms is starting to transform

this landscape. By aggregating informal riders, these platforms introduce

"soft formalization" with features like real-time tracking, digital payments,

and performance metrics. This hybrid model enhances efficiency and transparency

but also raises questions about the future of work for self-employed

contractors without formal employment benefits.

Systemic Frictions and the Path Forward

Nigeria's informal logistics networks present paradoxes: they are

indispensable yet inefficient, resilient yet reflective of state failures. Past

policies of neglect or eradication have largely failed. The way forward lies in

pragmatically integrating formal and informal systems.

Integration Imperative: Beyond Eradication

The historical approach of replacing informal systems with

"modern" formal infrastructure has failed, as exemplified by limited

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems that do not integrate with existing informal

networks. This flawed perspective misidentifies the informal network as a

problem rather than a vital system. A shift towards collaboration and gradual

upgrading is essential. Empowering operator associations, including the NURTW,

is crucial. Engaging these groups as partners can facilitate the introduction

of safety standards, driver training, and improved working conditions from

within the system.

The Digital Catalyst: Bridging Formal and

Informal

Technology is a powerful catalyst for transforming Nigeria's logistics.

Digital platforms are already bridging the formal-informal gap, creating

market-led pathways to efficiency and transparency. Freight-matching platforms

connect shippers with informal truck operators, and LMD aggregation platforms

organize informal riders for e-commerce.

These

technologies offer "soft formalization" through:

Transparency: Real-time

tracking, upfront pricing, and digital proof of delivery foster trust and

accountability.

Efficiency: AI and data

analytics optimize routes, reduce empty trips, and balance supply and demand.

Data

Generation: These platforms generate valuable real-time data on the informal

logistics economy, aiding private and public sector planning.

Supporting the adoption of these digital tools and collaborating with

operator associations can foster a hybrid logistics system that leverages the

informal network's strengths while mitigating its weaknesses, ultimately

supporting Nigeria's economic growth.